I packed up this operation and trucked it over to meganfindlay.com.

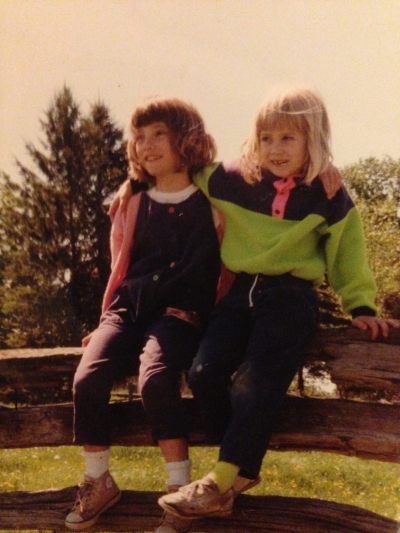

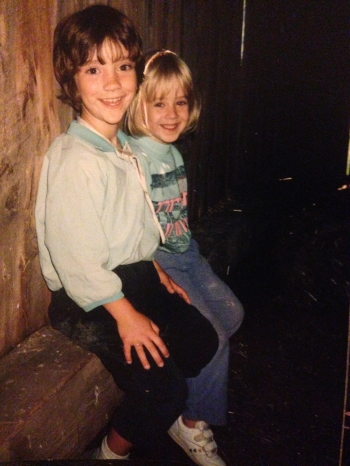

When I hear the phrase “innocence of youth,” I often think of the March breaks I used to spend with my cousin Leah.

Leah was a city kid and I was through-and-through country. Our parents traded us off from one March break to the next; she’d come and spend a week catching bullfrogs and building haystack forts at my farm one year, and I would spend a week rollerblading and going to the mall in her urban neighbourhood the next.

But our differences were greater than the Aesopian fact of our contrasting homes. I saw myself as an adventuring vagabond, a bit awkward, my crap-coloured hair forever a tangly mess, my clothes forever south of cool. Leah, on the other hand, was an adorable blonde pixie. She was adventurous too; the difference was that she had adventures while looking effortlessly fashionable and self-possessed (that neon fleece was so sick in 1990). I remember watching her bundle her hair into a perfect ponytail without even thinking about it, and reflecting on my own attempts to put my hair up, how it took the savage wrenching of a hairbrush from scalp to frayed ends, how it always ended up cockeyed anyway. I used to study pictures of her and her friends, pasted collage-style on a wall in her super-cool basement bedroom. There was one of her and a friend sprawled on the grass at Canada’s Wonderland, where I had never been. Something about the photo – their facile expressions, the arching spine of a roller coaster in the background – seemed so immensely cool to me, so intimidating. (Eventually, Leah and my aunt Susan took me to Wonderland for the first time, and when we posed for a photo in front of that big fountain at the entrance, I consciously tried to look the way those girls had looked in that picture).

Leah also owned things that seemed inconceivably exotic and unattainable to me: a water bed, an entire Playmobil city, a Gameboy and, briefly, an extremely awesome and enviable plaster cast on her right arm after I (allegedly!) pushed her off the roof of the chicken coop.

All of this might make you think that we didn’t get along. That I crouched jealously in her magnificent shadow, and seized whatever opportunities presented themselves (the chicken coop!) to exact revenge for perceived slights. But you couldn’t be more wrong. We were close in age and our mothers were sisters, which placed a sororal expectation upon us. But we went way beyond that. We shared an inventive and generous friendship, one that transcended (and was maybe even enhanced by) our differences. We played like no two kids have ever played before or since. We laughed until our ribs hurt. We had adventures. We missed each other when those adventures were over and we had to go back to our regular lives. I knew lots of kids whose cousins were close by, who would see them every day at school, but I didn’t envy them; even when I was small, I understood the magic of having Leah all to myself for very special, very concentrated periods of time throughout the year, our undiluted joy spilling into everything we did together.

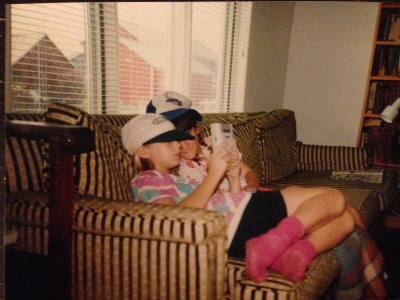

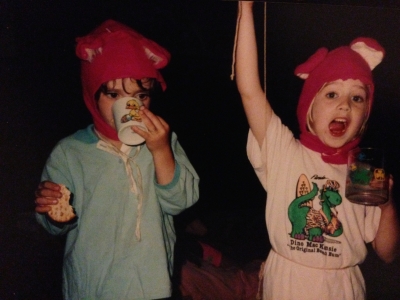

It was great to have Leah on the farm, but I loved the March breaks that we spent her house best. One year we built a go-kart in the driveway with my uncle Jim, then raced it down the street; one year we went to see the movie Heavyweights and I found out who Ben Stiller was; one year we got our hands on a bulk-sized box of Skittles and hid them in the heating vent, helping ourselves until we nearly dropped dead from a sugar overdose (to this day, the taste of Skittles time-warps me back to her bedroom). We made our own detective agency, inventively called”The L&M Detective Agency.” We recorded a giggly radio show called “Rotten Egg Yolk.” We played our favourite game over and over, which was called “Let’s pretend we’re orphans who are running away from the orphanage.” We tried using a Ouija board once, lying on our stomachs in the middle of her bedroom with candles lit around us, and got so scared that we had to shout for help. Once, Leah had a dream about a secret room behind her closet, and somehow persuaded my uncle Jim to knock a hole in the closet wall and, sure enough, there was a secret room behind it. It was a cold, drafty, odd-smelling crawlspace under the roof, and we thought it was perfect. We stuffed it with candy and Archie comics and called it our clubhouse.

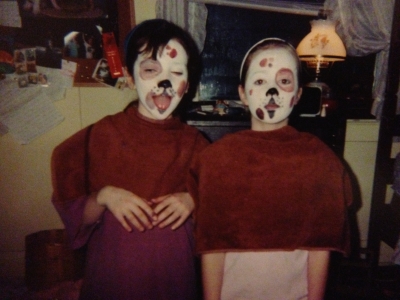

And apparently we dressed up as dogs a lot.

There was whole new set of words at Leah’s house that had a magical sound to them: Easterbrooks, the diner within walking distance where we went for milkshakes (I loved my farm, but the only place I could walk from there was to a muddy culvert under the dirt road, a good spot for playing but unlikely to yield delicious treats). Aldershot, the local high school with an indoor pool where we’d swim until our fingertips raisined and our eyes sealed over from the chlorine (once, waiting for our ride home from Aldershot, I experimentally dialled 9-1-1 from a pay phone to see what would happen, then panicked and hung up, then panicked again and ran away when the pay phone started ringing. Kids are so weird sometimes.)

Those March breaks are some of the best, happiest, most liberating times of my life.

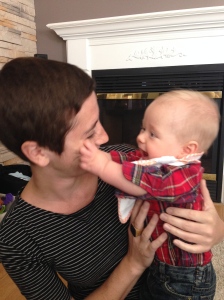

It’s almost March, now. Almost that time when, half my life ago, I would have been full to the brim with sweet anticipation of the week ahead. And the fact is that I am full to the brim with sweet anticipation, because on Sunday Leah’s little boy Carter is being christened and a whole pile of us are making the pilgrimage to be there for the celebration. And then, on Sunday night, Leah and I will have a sleepover together at my aunt and uncle’s house, almost like old times. It will be a celebration of the innocence of youth. Carter’s youth, of course. But also ours, hers and mine, and the memories we share.

Two strangers at the grocery store reach for the last pack of on-sale paper towels at the same time. It’s a sequence from some low-budget TV commercial we’ve all seen, right? Hurry before they’re gone! Or else it’s the climactic moment in a dribbly rom-com. Our eyes lock, our hearts melt, and everyone in the theatre needs a Bounty Duratowel ($4.99 this week only!) to sop up their happytears.

Well, you guys: this happened. To me. Only the first sentence, though. Not the TV commercial or the we-bought-a-farm-and-lived-happily-ever-after part. But I was definitely a stranger at the grocery store, and so was he. And we definitely reached for the last discounted pack of PC Ultra Absorbent at the same time. Then our hands shot back like we’d each been zapped. Stalemate politeness took over: Go ahead. No, you go ahead. No, really. I don’t mind. Each of us a martyr, considering the full-priced packs like they’re what we wanted all along.

He had a whiff of fatherhood about him. A grocery list in feminine cursive clutched in one hand. Unlaced Reeboks and a once-dapper leather jacket, which I imagined was concealing a spray of milky spit-up across his shoulder. When he came on this errand, he left behind a home in great need of paper towels. A home where a toddler was overturning a plastic bowl full of pureed carrot onto the dog’s head. A home where a bottle of Crayola finger paint was dispatched all over the bathroom tile. A home where kids tromped indoors before any adult could lasso them and remove their slushy boots, shake off their snow-clumped mittens, wipe their runny noses.

These visions set off a trio of reactions in me. First, generosity (“Seriously, I don’t need these as much as you do.”). Then, irritation (“You brought this on yourself, buddy. The full-priced towels are right over there.”). Then, of course, a grimy underworld of personal despair.

I buy paper towels because I need something to tuck into my shirt collar while I eat dinner in front of a book, or Netflix. Because I need to sop the grease off the bacon I’m using on my homemade pizza. Because I want to soak a few sheets in cold water, then wrap them around a bottle of white wine in order to chill it before I consume it in front of a book. Or, you know. Netflix.

In really desperate times, tweaking-with-loneliness times, I might need a paper towel to dust the plant leaves. Don’t go back and read that sentence again: you got it right the first time. I annoyed my cousin Anna with too many pestering questions about how to take care of all these plants I inherited, and as revenge she told me that I needed to keep them dust-free. You get ten whole points, Anna. And because I spent the hour between 2 and 3pm today listening to a podcast that I don’t even like that much, performing a futile chore that my cousin invented to teach me a cryptic lesson about not being so helpless all the time, I get negative five points.

Anyway. This Loblaws Dad and I. In one brief, charged moment, our worlds overlapped like a sloppy Venn diagram. There was his expansive circle, and here was mine; the thing we had in common was this pack of discounted PC towels. Maybe we each wanted what the other had. Lately, I can’t walk ten feet without meeting someone who is about to have a baby, or just had one, or is about to get married, or just did. It’s a sensitive area. And maybe he can’t leave the house without noticing people who are shopping for Doritos and cocktail mix.

I’m sure he could tell me something about sleepless nights and bottomless love, and I could tell him something about suddenly realizing that you’ve been dusting plant leaves for an hour. We’d each leave the other better off.

Spoiler alert: I took the towels. They’re my consolation prize; he already won.

Be the one on the social committee who volunteers to make caramel popcorn for everyone. To make caramel popcorn for everyone. Served in mason jars. Reject your friend’s hint that Costco sells caramel popcorn in four-gallon buckets. You do not want your colleagues to eat Costco’s caramel popcorn. You want your colleagues to eat caramel popcorn made with your blood, sweat, and tears. You want your colleagues to ingest your DNA as they eat the popcorn you made. How can they not love you if your DNA is part of them? That’s why people make babies. And labour-intensive popcorn.

Walk to the grocery store and buy every stick of butter you can find. Then ask the 12-year-old stock clerk if there is more butter in the back room. While he goes to look, pretend you are shopping for kale and granola, not twenty kilograms of salted Gay Lea. Look at the muscular kale shopper in the North Face fleece. Pretend not to care when he allows you a tight smile and then starts pushing that cart over there, the one with the adorable three-year old perched in the seat.

When the 12-year-old stock clerk inexplicably returns with an armload of Shreddies, spare his feelings by pretending that you were looking for Shreddies all along. He did not volunteer to be part of this, after all. But you did. You idiot.

Go home and cry a little into an expensive lotioned Kleenex. Life is hard! Men are jerks! There is so much popcorn to make! What’s that sticky feeling on the bottom of your slippers! Cuddle your cat, because everyone knows that only painfully cool almost-thirty-one-year-olds have overweight, entitled felines warming their feet at night, instead of human beings.

Feel vaguely gratified that you’ve taken care of the tears. Now you just need some blood and sweat.

Start melting all that butter on the stove. Burn it immediately. Break the smoke alarm while trying to twist it off the wall. Chase the smoke alarm’s battery, which has skittered across the floor and under the couch. Find it lodged next to a book you were reading in your former, more innocent life, before you lost your mind and volunteered to make enough caramel sauce to keep a carnival kiosk in business for a whole afternoon. Feel nostalgia for your former book-reading, nap-taking, leisure-loving self.

Ignore all the small print in the online recipe you found, because ain’t nobody got time for that. Ruin the first batch. Read the small print after all. Discover that you were not supposed to place pans of popcorn directly over the heat source.

Make a batch that tastes just like your mom’s and looks like the photo in the recipe. Do a victory dance. Scare the cat. Spend ten minutes reassuring the cat that he is loved and that there is nothing to be afraid of. Understand that in some deep, zen master way you are mostly reassuring yourself.

Measure your first successful batch. It fills exactly seven mason jars. Do the math (relying (only sort of!) on a calculator) and realize you will need to make popcorn for the next eighty hours or so in order to fill fifty-five jars. Make a list of how many colleagues you actually like. Like, like like. The rest get Shreddies.

No, seriously. Consider cheating by filling half of every mason jar with Shreddies. Text your friend to see if that would be acceptable. Accept that it would not.

Spend thirty-five minutes searching for good podcasts. It’s going to be a long night.

Realize you have just eaten a mason jar of caramel popcorn for supper. Resist giving a fuck.

Spend another twelve minutes finding something good on Netflix because you’ve listened to all the podcasts in the whole universe.

Look at the time. Panic a little. Start typing “quick and easy caramel popcorn” into Google. Stop after “easy” and let auto-fill do the rest. Realize your mistake after twelve minutes of learning how to make money, shed belly fat, and die in a hurry.

Feel overtaken by a frenzy of productivity and make seven more mason jars’ worth of popcorn. Like a boss.

Realize it’s already twenty minutes past your think-about-getting-ready-for-bed time and you still have forty-two mason jars’ worth of popcorn to make. Do another Google search. Discover that Costco closed half an hour ago.

Start writing a blog post about it because you recently paid to retain your domain name for another year, so better get your money’s worth. Feel proud that you are taking the creative lead in your life, turning gloom into art. Notice the last post on the website, from more than a year ago. Fuck art! Where did those lotioned Kleenexes go?

Play really old songs with really old meanings in really loud ways. If your neighbours don’t like it, they can move. Seven more mason jars filled, just like that. You’re getting into a groove. Dance a little. Scare the cat again with your jerky scarecrow dance moves. Let him deal with it on his own; he’s seventy in human years, after all. He should be comforting you.

Another seven jars! Maybe you should quit and become a candy maker. Like Willy Wonka. Nothing bad ever happened to that guy.

Burn the next seven jars’ worth. Decide to let it go. Then decide to turn this into a proverb: Sometimes life needs more dancing and less popcorn!

You were never good at writing proverbs.

Seven more jars! This batch burned just a little. Try a few pieces and decide to include it in the mix anyway. If you don’t go to bed soon, you might die.

Realize you’ve been writing your new blog post instead of making your popcorn, and also that you’re talking to yourself like a crazy person. But maybe making this amount of popcorn already qualifies you as a crazy person, so the talking really doesn’t matter.

Seven more jars.

Seven more jars.

Seven more jars.

You’re a robot now. Void of all feeling. Pop the popcorn, make the caramel, dribble it together, shake it up, stick it in the oven, take a break.

Look frantically for the cat, like you do several times a day. Find him cowering in the boot closet. Reassure him that there will be no more dancing. Reach a tentative kind of truce. He affords you three licks and a bite. Another proverb? No – you are terrible at those.

Eat a handful of baby carrots and half a can of flaked albacore tuna as penance for all the scarfed caramel sauce. Feel a particular kind of roiling in your guts. Admonish yourself. If you were a true adult, you would be eating real meals. Or feeding real meals to a tribe of small children. Admonish yourself again—if you were a true feminist, you would not base your self-worth on making babies. Admonish yourself a third time: if you were true to yourself, you would have ordered Dominos. Why didn’t you order Dominos?

Seven more more jars and OMG is it possible you are DONE? Package it all up in a white garbage bag, the kind normally reserved for kitty litter. Stop to ponder this for a moment. Sometimes life gives you a bag of sweet, sweet candy, and sometimes it gives you a bag of shit.

Feel immoderately proud of yourself. (For the popcorn and the proverb.)

Resolve to imagine, for the time being, that you employ an enthusiastic maid who will have all of this cleaned up by morning.

Sleep. Dream. Wake with indigestion and a vague sense of things going wrong. Feel the cat shifting against your feet. Tell yourself that everything will be okay, and everyone will have popcorn, and you will never again have to listen to the reproachful whirr of an air popper.

D is (somewhat temporarily) living in Vancouver for a few weeks each month. On the scale of problems, this one rates fabulously low. There’s a certain quiet pleasure in missing my favourite man for three weeks and spending the fourth right beside him. It’s a rhythm I could get used to (for a while). Heartsickness. Reward! Heartsickness. Reward! Everyone goes through this cycle to some degree, and somehow I bumbled into the good luck of knowing when my reward is going to arrive. Every month or so, bleary from a red-eye, wearing a crumpled blazer, pulling me in, smelling deliciously like himself. That is not a problem.

D is (somewhat temporarily) living in Vancouver for a few weeks each month. On the scale of problems, this one rates fabulously low. There’s a certain quiet pleasure in missing my favourite man for three weeks and spending the fourth right beside him. It’s a rhythm I could get used to (for a while). Heartsickness. Reward! Heartsickness. Reward! Everyone goes through this cycle to some degree, and somehow I bumbled into the good luck of knowing when my reward is going to arrive. Every month or so, bleary from a red-eye, wearing a crumpled blazer, pulling me in, smelling deliciously like himself. That is not a problem.

Rolling over in bed and stretching my hand into that cold tundra of mattress beside me: that is the problem. I don’t want to be someone who can’t function without her man, and this momentary reshuffling of our lives is a good time to assert that I’m not that person. But I can’t help feeling like Dumbo and the magic feather. He can fly if he’s holding it; he will fall if he’s not. Logic and physics are feeble defenders against white-knuckled faith. Sometimes I feel inadequate to all that daily life requires of me, particularly in those first few days after he has to leave again, when everything still has his shape.

I met D when he was drawing comics and I was writing solipsistic personal essays (and still am! hello, blog!) and we fell in love gradually, in our pajamas, watching The Sopranos and VHS movies.* For a while he had a habit of knocking on my bedroom window at 3am until I went around and unlocked the door, and then he would sit on my bed next to a much younger Tycho and force-feed me cinnamon butterhorns from the 24hr A&P. And that was pretty great. But the thing is, when you’re 20 and eating butterhorns at 3am with a cute boy, you have no capacity to really understand what the hell is going on. You believe you are young and edgy and this sort of unpredictable shit is going to keep happening to you forever. When you wake up and roll over and discover a cute boy’s face framed in your bedroom window, you can’t tell that you’re looking at your future. You can’t tell that ten years later you will still be waking up and rolling over and feeling that all-over joy of having that cute boy around. Except—not around.

*(Whenever I need a reminder of how long I’ve loved this guy, I think about him fixing the VCR at my ramshackle undergrad house so we could watch Cube (a priority for some reason). One day we will brag to our kids that we loved each other when there were still VCRs, and when people still blew into Nintendos, and when no one had cell phones so I had to get used to talking to his parents on the landline.)

There are benefits to all this! For one, he is having the time of his life. Job, friends, ocean, something called Japadogs. When I went to see him last month he practically turned himself inside out trying to show me all the things he loves about the west coast, and my legs fell off from all those Stanley Park miles. Normally I am the one to bring the outclassed enthusiasm to any event; it’s a novelty to see him so overtly gratified.

And life is mostly sunshine and candy for me, too. Fabulous new job that still makes me weak-kneed with happiness. A gorgeous, enormous apartment that I get to live in on my own without paying the rent on my own. Big and little plans that take over the controls just when I’m about to implode with loneliness. And the cat, of course, claiming D’s empty black office chair with a donut-shaped ring of white fur like it’s been his forever.

D would be happier if we were together, and sometimes knowing that is enough. This is not a problem. It’s just momentary reality.

And in the meantime, I have filled that empty half of the mattress with books, which may not give off as much warmth, but they don’t tickle and they go to bed at the same time that I do.

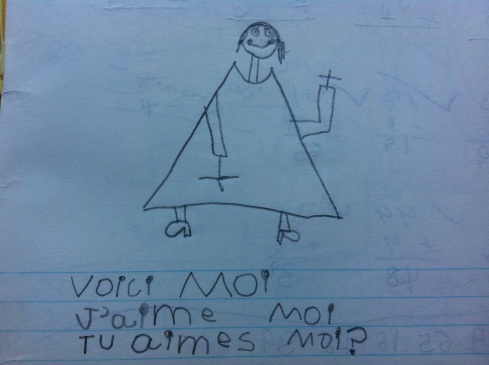

Exhibit A: The neediness that began in Mme. Henry’s Grade 2 French Immersion class and has never really abated. Also, this might be the only time, in fiction or fact, when you will see a rendering of me in heels. TU AIMES MOI?

I started a new job two weeks ago and I am, as I’ve said to anyone who’s asked, dreamily suspended in the glowing, embryonic honeymoon stage of love.

The feeling around my new workplace is very “be who you are.” There is no sanding down the edges, no drinking from the same punch bowl. You identify as nerdball? Fly that flag, brother! Call yourself literary? Here’s the perfect spot for your vintage Olympia. We all grew up on the “you are special” curriculum and now, somehow, we’ve stumbled together into a workplace that lets us be as affectionately peculiar and obsessive and eclectic as our special A+ hearts desire. It’s wonderful. And, to borrow from the parlance of the industry, it drives results. Clients are happy. We are happy. Every day is like a long, rib-cracking, down-home group hug, with beer on Fridays.

But here’s the question: where do I fit into that?

Here is the question again, this time demonstrated visually:

Two empty shelves on the wall behind my desk. I have to decide what to put on these shelves. And whatever I decide – even if it’s nothing – will broadcast something about me.

I could be anyone to my new colleagues. Only a couple of them really know much about me personally, and what they know I’ve managed to control in the low-lit bars and plushy living rooms where we’ve hung out, in manageable chunks of time, over vessels of alcohol that help me sustain an aura of writerly pensiveness. But now we’re going to be together for forty-plus hours a week, and only a few of those will be fortified by vessels of any kind. I need to decide. Yes, of course, I will be myself. But which self should I be? And how should I express that on these three parallel plains, which will shout my identity (such as I curate it) to the whole office?

Current (and woefully predictable) shortlist of ideas:

1. A carefully selected mini-library. This presents its own agony: what do I want the chosen titles to say about me? Is Alice Munro too predictable? Victor Hugo too pretentious? What about Strunk and White? Too didactic? Or should I really commit to flying my flag, and include my boxed set of 90s-era YA and Degrassi DVDs? I am paralyzed by indecision.

2. Pug stuff, starting with a pug-shaped bookend that sat in place of pride in my last office. But even I am finding the fact of my pug love, contrasted by the lack of a pug of my own, increasingly tiresome. And there is the danger that I will give my new colleagues this one very plain, 2-dimensional fact about me and will forever receive pug paraphernalia at every occasion as punishment. (Not that such a state of affairs would be at all difficult to endure!)

3. Paris stuff.

Taken on its own, not one of these three themes really tells a complete story, and I am afraid of creating some kind of clichéd pigeonhole in which I’ll reside forever. Is that where I want to begin with these nice new people?

Seems to me that it was easier to have an identity when we were all little kids and no identify was expected of us. Our parents chose what was put on display in our bedrooms, our teachers chose the wall art in our school hallways, and all we had to do was learn to add and divide, turn bread mould into science, and spell ten new words a week. In that kind of environment, we really could be whatever the hell we wanted, and it was okay if we changed our minds daily. I went through the usual fluid succession of career identities that other girls my age went through (what the hell made us all want to be marine biologists in grade three?), but even then I sort of knew.

Well, not sort of. I knew very, very specifically. I was going to be a writer. It seemed as easy as that to me: this is what I am going to do, this is who I am going to be. After all, when you were a kid, it didn’t take much to “be” anything at all. Want to be a firefighter? Here, put on this red plastic helmet and bash these toy fire engines around. And if you wanted to be a writer, all you had to do – in my estimation, anyway – was announce the fact to your whole class during the sixth-grade public speaking competition. And because I was already cultivating the bad habits that still plague me today, I went several hundred feet too far and used that speech to give myself very specific context: I would not only be a writer, but I would be one who lived in Newfoundland (somehow lodged in my brain as a place of fog, friendship, and free-range seaside adventure, sort of a benign Lord of the Flies) in a house that would be half on the ground and half hanging out over the edge of a cliff (I never won any prizes for engineering).

These facts were all enthusiastic elements of that sixth-grade speech, along with some whole-grain details about Newfoundland’s natural history which I used to sneak the real message past the academic gatekeepers. And the real message was this: Whether you are twelve years old or twenty-nine, discovering the identity you want to broadcast to the world doesn’t have to be complicated. Just make it up and give it a mansion on a cliffside. Or three deep, wide shelves on the wall above your desk.

Did you know that Stephen King is the author of more than fifty books? I am the author of exactly zero books. And this is why Stephen King is allowed to publish something with the uppity title of “On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft,” and people will read it by the millions and quote it to one another and even pay for it. I, on the other hand, with my exactly-zero-books, can only publish a blog post with the self-effacing title of “I Am Writing a Thing,” and people will maybe wander over to it when they are bored and quote it to no one and pay nothing for the privilege.

This thing that I am writing is not a book (though I can hope it might be, one day), but it is a written thing, and it has characters and dialogue and tense, rife-with-feeling plot development. It stars two high school seniors named Celia and Curtis, who tell their stories in alternating chapters, because this is something that Julian Barnes does. And if you have to start somewhere, why not start with one small toe planted in the enormous, Booker-winning shoes of old JB? So, Celia and Curtis. They are very much the opposite of one another, because opposites are interesting. But they are giving me a hard time. They are evasive and private, and I cannot quite wrestle them to the ground and force them to tell me who they are. So I have taken some advice left behind for me in a dismal grad school classroom: I am staging conversations with my characters in order to get to know them better. It’s a fun exercise because I get to enjoy the virtuous feeling of writing something without the annoying self-doubt of writing something that might actually be part of The Thing.

Me: Who are you?

Celia: Celia Birkshire Craw.

Me: Let me write that down.

Celia: Birkshire is a stone fence. Craw is a manure pile.

Me: Is that so?

Celia: That’s how I see it.

Me: And what about Celia?

Celia: Celia is a disease. But I like it.

Me: You like having a name that sounds like a disease?

Celia: You know how many Julies there are in my graduating class? Twelve. I would rather be my own remarkable disease than share a lame one with millions of others. People, medical people, write papers and articles about rare diseases. No one writes about the common cold.

Me: Is that how you see this project? Like a study of you, Celia Stone Fence Manure Pit, a rare thing.

Celia: Me, and Curtis Langford.

Me: Yes, you and Curtis.

Celia: [brooding silence]

Me: You don’t want to share this project with Curtis?

Celia: I just don’t get it. Why him? He’s such a dude. He’s vacant.

Me: What do you think he would say about sharing this project with you?

Celia: That he’s humbled to be considered worthy. Except he wouldn’t know what those words meant.

Me: Actually, I did tell him.

Celia: And?

Me: He gave me a blank stare.

Celia: See? Nothing going on.

Me: And then he said —

Celia: Don’t.

Me: Don’t?

Celia: I already know what he said.

Me: What?

Celia: He said, “Wait, you mean that faker chick?”

Me: What does that mean?

Celia: I might as well tell you, since you’re making this all up anyway. I used to pretend I was sick.

Me: Sick with what.

Celia: I dunno. Anorexia, brain tumours, tourettes (that was a fun one). Whatever came to mind.

Me: Is that the affliction you want to have? A tendency to fake illness?

Celia: Do I have a choice?

Me: Nothing’s really been set in stone yet. We can make changes. We can edit.

Celia: Hm.

Me: But you need an affliction. Something to overcome by the end.

Celia: Maybe I could be religious. Or an orphan? Or a lesbian? Curtis would say, “Wait, that orphaned religious lesbian chick?”

Me: I want you to pick one, Celia.

Celia: This is boring.

Me: Writing a book is mostly boring.

Celia: Then why are you doing it?

Me: This is about your motivations, not mine.

Celia: But who am I?

Me: Who are you?

Celia: I’m lonely.

Me: You are?

Celia: There you go. My affliction: loneliness.

Me: That’s not very unique. I want you to pick something between “orphaned religious lesbian chick” and “lonely chick.”

Celia: Go talk to Curtis. I’ll get back to you.

I got a mysterious phone call again. I hoped it was Katya, rescinding her abrupt dismissal from the last and only time we talked, but no: it was “Shannon.” And it was a voicemail. Shannon gets down to business.

“Hey Megan. I work at Al’s Diner. Your bus pass was found outside. I won’t mail it because it expires at the end of November, and it probably won’t reach you before then. So it’s at Al’s Diner at 834 Clyde Avenue. Just say that Shannon called you and it was behind the bar.”

TONE: Warm and understanding. Shannon has possibly been on the losing end of the bus pass life cycle herself, so she empathizes. I am touched by the small but not insignificant chain of events that led to this phone call, like a Rube Goldberg machine that is triggered when I characteristically fumble my bus pass to the ground without even noticing. Shannon has to pass at just the right place to see it; she has to not be distracted by the flotsam of life swimming through her mind at that moment; she has to bend down, pick it up, brush it off, locate my phone number, and call me.

“Hey Megan.”

Interpretation: Shannon is a keen observer. She could have just said “Hello.” But not Shannon! She used my name, and the familiar “Hey.” She probably deduced from my bus pass photo that I am a “Hey, [your name]” sort of person. I am not a “Good afternoon, madame” sort of person. I like Shannon right from those first three syllables.

“I work at Al’s Diner.”

My heart swells: she is like a John Cheever character. The romance of the working class. She has nothing to hide; in fact, she and Al maybe even be in cahoots. Do I detect a hint of intrigue in the way she rolls out the open vowel on “Al”?

“You bus pass was found outside.”

Shannon is humble. She does not seek credit for her nobless; she does not say, “I found your bus pass.” She is only a regular girl trying to do regular good in the world.

“I won’t mail it because it expires at the end of November, and it probably won’t reach you before then.”

I’ve had boyfriends who were less thoughtful than this stranger.

“So it’s at Al’s Diner at 834 Clyde Avenue. Just say that Shannon called you and it was behind the bar.”

Ten seconds earlier, I did not know that Shannon existed; now I am on a mission, and her name is the code-word.

I go to Al’s Diner on Monday morning. I pay for the bus with laundry change. As I weave unsteadily down the aisle of the 85, I begin to feel a familiar sense of painful self-awareness about my get-up. My only boots are the size of tractor tires and are really only suitable for the most blizzarding of days. Today, they are overkill by a long shot. The problem is that I always look out the window at the dog-walkers to gauge the weather, but the dog-walkers have become unreliable. After all, they are outside at 6am; who cares if they are wearing enormous overstuffed parkas and their castoff Sorrels. All fashion bets are off at that hour. By the time I am wrapped up in their image, they have deposited their dogs at home and have transitioned to pea coats and slender boots with artisanal stitching. I, donning my tractor tires and overstuffed parka, feel cruelly misled.

I find a seat on the 85 and begin the complicated process of unzipping and unraveling and untying my outermost layer so that I will not arrive at Al’s Diner like a perspiring Yeti. This makes me remember the two years I spent commuting to school on the metro in Montreal. To get to the metro platform, you had to descend miles and miles of escalators, and with each plunging foot the ambient temperature boiled one degree hotter. It was like descending into Hades. By the time you reached your train, you were lucky if you could still stand upright and string a sentence together in the heat. People shed clothes down there faster than a dancer on two-for-one night. Oh, Montreal. Thinking this way triggers a landslide of nostalgia for my old apartment, my old route around the city, my old friends. I look out at boring old Ottawa and sigh to myself.

But it’s the first wintry Monday of the year in this city, and as people shuffle around the bus to make room for one another, and as I stare out at a child’s first meager attempt at a snowman, a surge of generosity towards the city replaces that morose nostalgia for somewhere else. Look at all these good people putting their own small imprint on the world! Finding each other’s lost bus passes, and avoiding elbowing each other in the face when the bus stops, and generally looking out for each other’s welfare! It’s a good place, this world. It’s not a bad world after all.

I get off at my usual stop, Carling & Clyde. Pizza joints, a martial arts studio, a sprawling hardware store with slick, airlocked automatic doors. Al’s Diner is within sight. I jaywalk next to a guy who also got off the 85. He is thuggy and hooded. I marvel that we are sharing a common experience, even one so insignificant as jaywalking. I imagine that I get clipped by a U-turning minivan and he is the first one to reach my prone body. I imagine looking dazedly up at the sky, and then up at his face as he leans over me and shouts something. He is not thuggy after all. He is kind, and a leader. He orders someone to call 911 and he takes off his jacket and pillows it under my head.

We reach the other side of the road and I hurry off towards Al’s Diner without looking to see which way he goes. Sometimes I worry that my daydreams are intense enough to become visible to the people around me.

It’s quiet in the restaurant. A waitress – I can tell it’s not Shannon – nods to me. Somewhere a radio announcer says, “… and that’s not the only thing you’ll have if you subscribe today.” It’s still early, and all the tables are tossed in morning sunshine. Almost everyone is eating alone. Almost everyone is reading a newspaper. I remember the girl at my bus stop who hands out free copies of 24. She is not allowed to leave her post until all her issues of 24 have been distributed. When buses arrive and disgorge their passengers, she waves the paper over her head like it’s a white flag. Every other person plucks one away from her, and when that happens she leans down and takes another from her pile to wave around. The 97 bus is her best bet. She unloads at least a dozen papers each time one of those pulls up. I sometimes take one out of sympathy.

I sit alone at my little table in Al’s Diner. I see a solitary man eating blueberry pancakes just off to my left. Like me, he is without a prop. His hair is still damp and holds the track-marks of his comb. He has draped his coat over the chair opposite him. While he cuts his pancakes, he looks intently down at his plate. While he chews, he stares at his coat. He moves his head this way and that as though conducting an inquisitive, illuminating conversation with a companion who is visible only to him.

I sometimes worry that my friends are only my friends because we’ve been around each other for so long, and not because I am particularly likeable.

There’s a large-screen television hanging mutely over the dining room, tuned to TSN. I watch the Argos silently win the Grey Cup over and over. When the waitress comes – she is too old to be Shannon, surely – I order the Eggs Bennie for $9.99. The waitress is kind. She says “Cold, eh?” to every single customer as they come in, stamping their boots on the mat. She rests her hip against the table where the man with the comb tracks sits. She gestures with the coffee pot like it’s an extension of herself. I overhear her tell him that today is her Friday.

There are more people than cars in this neighbourhood of garages. I look out at the cars. Someone reverses a Dodge Caravan from the guts of a repair shop opposite Al’s Diner. For now, there is no other traffic. The driver turns onto Clyde Avenue and does a slow, lazy donut, then steers back into the garage, tracking a web of snow onto the clean pavement inside. The massive door rolls closed behind him.

My eggs arrive, and the man with the comb tracks plucks his jacket from the chair and leaves. After he’s gone I feel an odd sort of bereavement, like you do when you look one last time at the empty photo window of a wallet you’re about to toss away.

I don’t really believe what I thought just now about my friends. I remember that my bus pass is here somewhere, in the restaurant, and I feel even happier. I begin making to-do lists in my mind for the week ahead. It will be dark by the time I walk back along Clyde Avenue towards the bus stop that evening; I try to concentrate on everything that might happen between now and then, so I can be prepared.

The eggs aren’t bad. The night before, I had made pizza. All of it. I made the sauce, and the dough. D and I ate it until we almost burst. I think of the eggs sliding down and landing on top of the pizza and I experience a moment of queasy doubt about my breakfast, but that passes. I work out; I metabolize. I feel a rare surge of total self-reliance and I try to work out where it has come from, and how to reproduce it when it’s really necessary, in the more frightening moments of the Monday-to-Friday circus. The deadline moments, the Prove Thyself moments.

And then I see her: Shannon. She’s behind the bar. I know it’s her. She’s taking care of her section of tables efficiently and kindly, just like she took care of me.

I wait a long time for my waitress to bring the debit machine, and while I wait I watch Shannon. I look at the bar and think, the bus pass that was once on my bedside table is now behind the bar at Al’s Diner. When the debit machine comes, I leave an enormous tip, hoping some of it will spill over to Shannon, but also feeling some grandiosity for my own waitress who, for all I know, taught Shannon her good and giving ways.

At the bar I catch her eye. I say, “Shannon?”

She looks at my blankly. I falter. I explain quickly and inelegantly about the bus pass.

“Oh,” she says. “It’s Sharon, actually. Not Shannon.”

I try to affix this new name over the place where I’ve already got “Shannon” tattooed. She sees my struggle and says, “I mumble a lot.”

In the end, it’s an unceremonious event. She flips through some clutter on a shelf against the far wall, finds my bus pass, extends it towards me. I take it and say something like, “I’m always losing this thing.” It’s the wrong thing to say; she thinks I’m a twit. And she needs to get back to her tables. “Thank you,” I say, and at the very same moment she says, “No problem.”

In my overstuffed parka and tractor-tire boots, I push out of the restaurant turn towards my office and the waiting mystery of this new week.

My dog Kelly got hit by a car on November 18th, 1991, just a few days after my eighth birthday. I watched through the family room window as my dad carried her away from the road and set her down on the lawn. She did that heartbreaking dog thing of thumping her tail on the grass, even though she could hardly lift her head. My dad rubbed her ear between his thumb and finger. I understood, even at age eight, the magnificence of the moment: the thump of her tail, the movement of my dad’s hand on her ear, the look on his face as he stared at the highway where she had been struck, like he was resigning himself to the calamities that life had already dispatched but that had not yet arrived. I understood, my nose pressed to the glass, that something very important was being decided. Our asthmatic old pug, Mim, chortled around at my feet, and I reached down and rubbed her ear between my thumb and finger, perhaps thinking that I might channel some of what my dad felt by mimicking that slow, sad gesture of his.

It is not true that farmers are used to death. It is only true that they are used to pragmatism, and it is this pragmatism that forces them to endure more loss and grief than the average person should be expected to face.

My mom had replaced my dad next to Kelly’s motionless body – motionless except for the thump, thump of her tail – while he ran to get the truck. I stared out the window and tried to imagine doing all the things I usually did with Kelly, but doing them alone. My “patrols” of the fields and the creek bed, my little jobs of stacking wood and feeding chickens, my daily walk to the foot of the driveway to wait for the school bus. We had many animals on our farm, but only one of these animals really felt like mine. My sister had the cats. My parents had the pug. I had Kelly. Or I did.

At the family room window, I felt myself accelerate from parodying the grief I’d seen displayed by adults to experiencing it for myself, and this was a new and alarming feeling. All of a sudden I saw, in some early, elementary way, that in addition to cartoons and chores and school and basketball, life would also involve loss. And that there was a special sort of loss attendant to watching a pet disappear. (This moment was big enough for me to remember it eight years later when I was reduced to hyperventilating sobs at a plastic table in the Dundalk Public Library, rubbing the last page of Where the Red Fern Grows between my thumb and finger.)

At some point after he came home from the vet’s without Kelly, my dad had likely sat down at his desk, selected one of his ever-ready needle-sharp pencils, and recorded the expense in our household ledger. I imagine him assigning it some circumspect category like PETS – OTHER EXPENSES. I made my own record of the event in my daily journal at school. I think, even at age eight, that I recognized the inadequacy of my teacher’s comments.

For the first time, I was experiencing the way that nonsensical tragedy can scrub your mind clear of all of life’s trivia, of everything you had mistakenly considered important until that moment. The day that Kelly was hit, my barely-eight-year-old brain abruptly demoted several items that had entirely absorbed me before that moment, like what to request for Christmas, and whether my dad would inspect the vacuuming job I had hastily completed that morning. It took my whole miniature brain to receive and process the unfathomable fact of Kelly’s sudden disappearance from my life.

It’s not like death was an entirely novel concept for me. I had seen my dad drive off to the abattoir with a truckload of pigs, and I had seen our freezer fill with packages wrapped in flesh-toned butcher paper, and I had completed the equation for myself. But, as we all know, there is death and then there is death. Understanding this was terrifying and lonely, but, like the first time in your life when you receive bad news on the telephone or attend to a skinned knee without any adult help, it also felt exhilarating and grown-up. I looked at our war-torn tabby farm cat, Zeeklink, and thought: You are going to die. I looked at Mim and thought, So are you. (Fortunately my family and I did not have to deal with those two certainties for quite some time, though Zeek would eventually meet her end the same way Kelly did, on the two-lane rural highway at the perimeter of our farm, the only part of the RR#3 landscape I was glad to leave behind when we moved.)

Maybe I’m making too much of this. It’s hard to know, from a journal written in third-grade English, if I really felt any of these depths I’m describing. I remember more distinctly how much I loved Kelly while she was alive than how much I grieved for her after she died. So maybe I’m missing the point: maybe this story is not about the end of innocence, but instead about innocence itself, and how a death that would be crippling to me now was somehow more manageable then. After all, the next day’s journal entry is about how much I liked Zoodles for lunch. Maybe we are able to let go more gently when we are children, to fold sadness and loss into our experience alongside happiness and canned delights. Maybe, as adults, we can draw some resilience from this fact.

But I remember standing in that family room window so well. I remember watching Kelly thump her tail while my mom and dad moved her onto a blanket and lifted her, like a baby in a sling, onto the seat of the waiting truck. A memory like that doesn’t stick around for nothing. It has lasted with me. So has Kelly, especially at this time of year.

What’s that you say?